If you are about to hand over your private details in exchange for a store loyalty card, are you confident that your data remains in safe hands?

It can be difficult to predict if the supermarket manages your sensitive details securely and responsibly. The company may store them on vulnerable servers waiting for hackers to attack. Also, your data might be sold to data brokers for things like targeted advertising and political purposes. Companies are often opaque with their data management practices, and it can be difficult to understand what is happening once our private details are handed over.

This article borrows a few solutions from economics and attempts to apply them to questionable data handling practices.

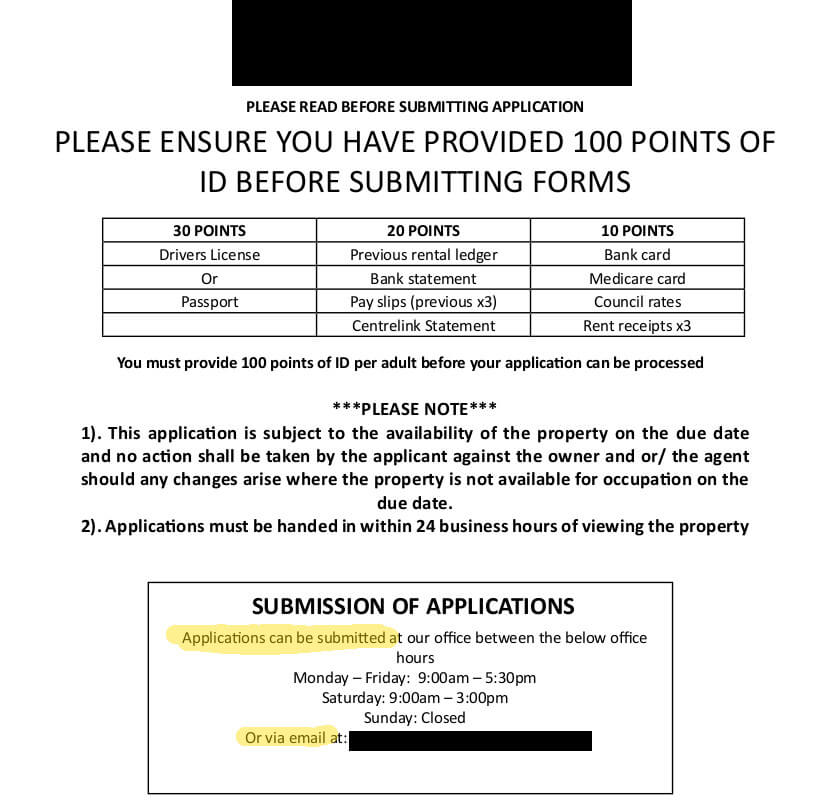

Identity Verification in Australia

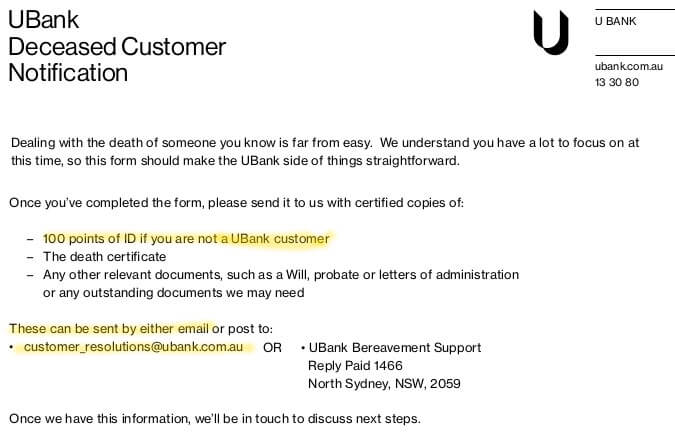

One of my pet peeves is the ‘100 points check’. In Australia we rely on this personal identification system for things like job applications, rental agreements, bank and credit card applications or managed Bitcoin wallet applications.

This identification procedure has been in use since 1988, when home computers stored data on cassettes, and the primary display of a home computer was a TV set. Today, even though many organisations or transactions do not have legislative requirements or reporting obligations (such as banks) to require a 100 point ID check, many organisations ask for it anyway, just to make sure they know they are really dealing with the right person.

Bad Practices at a Real Estate Agency

So, I applied for a lovely apartment recently, which is already a stressful procedure on its own. As part of the rental application process, I was asked to provide a stack of documents to the real estate agent including: a scanned copy of my passport, driver’s licence, Medicare card, and bank statements.

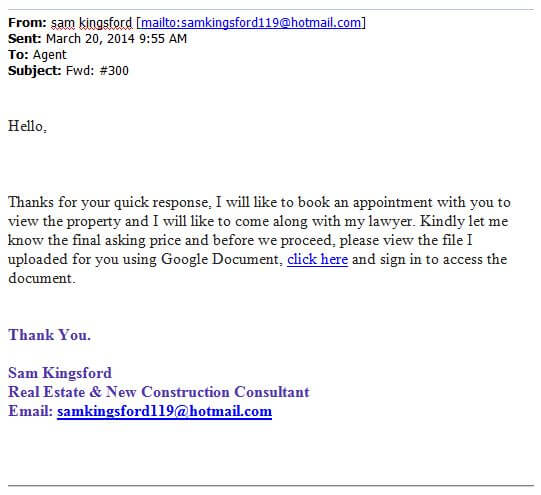

The first shock came when I was instructed to send these documents in a simple email. To make matters worse, I had to do it even before I was shortlisted as a potential tenant. Considering that about 20 people had turned up on the apartment viewing (Sydney… doh!), the agent would be receiving hundreds of email applications per day with all sorts of sensitive documents attached.

As a security professional, I began to worry about the long-term fate of my documents. Questions were racing in my head: Is my real estate agent going to store my documents on an encrypted drive or just in a shared S3 bucket with some misconfigured permissions? Will the agent share these files with third-parties and how? How secure is the agent’s email server? Will my email and sensitive attachments linger around in the agent’s inbox waiting for a hacker to take the email account over? Will I be notified if my personal details are compromised?

This situation was an example of the information asymmetry between my real estate agent and me. The agent knew what would happen to the documents once they were sent in, while I did not. Now, this imbalance allows my agent to spend as little as possible on good security and privacy practices. What is more insidious is that it enables them to sell my data to data brokers and marketing agencies, without my knowledge either legally or illegally. So what can we do about this? Fortunately, this is a well-explored area in Economics called ‘principal–agent problem’ and it is solvable.

Borrowing Ideas from Economics

The ‘principal–agent problem’ occurs when one party (the “agent”) has more or better quality information than the customer (the “principal”). Agents acting on behalf of the customer may exploit the situation if the incentives are not set right.

For example, a taxi driver, who knows a city like the back of her hand, may rip off her passengers who are unfamiliar with the city. Restaurants may relax on their hygiene and food safety standards because their patrons cannot see what is happening in the kitchen. This conflict of interest is also known as ‘moral hazard’.

In general, the same situation applies when we trust companies – like my real estate agent – with sensitive information. If the agent had the incentives to manage documents securely, they would probably need to hire a security expert. The expert would set things up like a secure file sharing solution, two-factor authentication and introduce good data disposal practices. The problem is that these additions cost money and real estate agents are incentivised not to foot the bill. In other words, my real estate agent is not interested in protecting my data, but signing rental agreements for as many apartments as possible in the shortest amount of time.

How We Can Solve the Information Asymmetry

To eliminate the moral hazard problem, we have to either lessen the information asymmetry or change the incentives. Customers either have to understand what they are getting into, or companies need to be interested in good data management practices.

Before we explore the various options, just a word about public shaming. The usual media circus after a data breach is rarely effective. Apart from a few exceptions, companies never go bankrupt, stock prices are not significantly affected on the long-term, and the number of customers bounces back eventually. The general public are quickly desensitised by the continuous news of data breaches, or the attention soon shifts to the latest data breach.

Solution 1: Education and Transparency

The first solution to the moral hazard problem is a combination of education and transparency. If customers knew what the proper data management practices are, and they could observe them in action, customers would be able to make informed decisions. Ideally, customers should recognise if something is wrong before they hand over their personal data.

As for my real estate agent, I knew that the practices were terrible. It was clear to me from the start that the agency was applying lousy information security practices. Emails with sensitive attachments is a no-no as they are not encrypted en-route. Furthermore, copies of the emails linger in the sender’s outbox and the recipient’s inbox. If one of the mailboxes is compromised, the documents can easily be retrieved. As for transparency, I had no clue where my files would be stored and how they would be disposed. I could only assume the worst.

The problem is that I spent about a decade in the information security industry. Without boasting about my skills here, it is unrealistic to expect from everyone to be an information security expert. Even if the company is fully transparent, one would need a high-level of technical knowledge to understand what is going on. Most of us, understandably, are not willing to invest years in understanding secure data management practices and have better things to do. Education may work in simple situations, but not this one.

Solution 2: Rating Sites and User Reviews

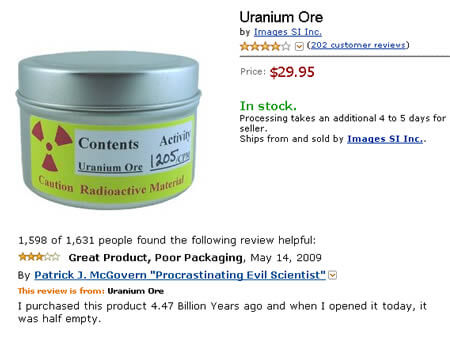

The second option is lowering the incentives to exploit the information asymmetry situation. For example, rating sites like Yelp! makes restaurant-owners interested in providing a better service rather than cutting corners here and there. If a restaurant is continuously getting bad reviews for the overall experience, it will soon go out of business. Amazon, Airbnb and eBay are also good examples how poor user-ratings can drive sellers with poor practices (as known as ‘lemons’) out from the market.

We should let customers rate companies by their privacy and data management practices. Does a company have an upload portal for sensitive documents? Is strong authentication (e.g. two-factor) available? Is it easy to delete an account? Five stars! Does the loyalty program sell your personal details and your purchase history to data brokers? Is the business asking for more information that it needs to provide you its service? Booo, 0/10!

Recently, security blogger, Troy Hunt went as far as suggesting to put warning labels on IoT devices:

Hey @vtechtoys, how about put this warning on the box so it can be seen before purchasing? Yeah, didn’t think so… https://t.co/erdFdUp4jS pic.twitter.com/qRUUCmz1SY

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) October 12, 2017

On a related note, the OAIC Notifiable Data Breaches scheme could also serve as a some kind of rating system. From 2018, Australian companies earning over $3M in revenue will be required to submit a formal report to the Information Commissioner in circumstances where they have been hacked and personal or financial data was involved. If I could simply look up how many times my real estate agency was affected by a data breach, I would certainly pick a different company if they had previously been involved in a data breach.

Solution 3: Certification Programs

The third option is a licensing scheme, in which independent third-parties could review and enforce good data management practices. Certifications can reward and enforce good practices in other industries. For example, taxi drivers cannot even operate without a licence. Mandatory certifications can guarantee and enforce a minimum standard of service within an industry.

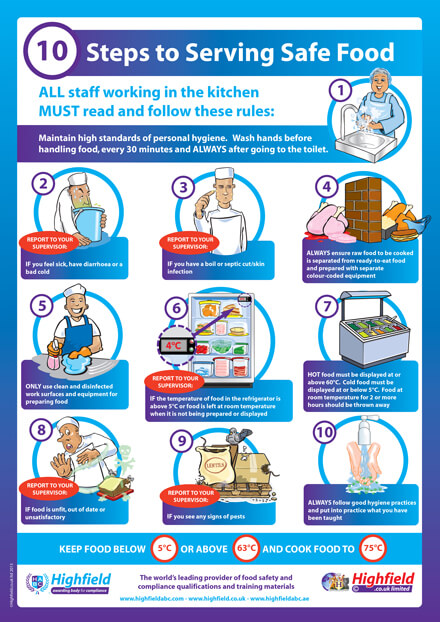

Another successful certification program is HACCP, which keeps restaurants clean around the world. This certification scheme prescribes food handling and good hygiene practices that keep customers safe from biological hazards. Some of the rules may seem bureaucratic and cumbersome, but at the end of the day, patrons do not usually leave HACCP-compliant restaurants with food poisoning.

We could apply the same approach to companies handling sensitive personal information. For instance, we could let an independent body tell us whether a company is managing sensitive data responsibly. What if all organisations that carry out the ‘100 point ID checks’ had to be compliant with a collection of rigorous security practices? What if my rental agency would not be allowed to process documents for the 100 points check if the company was negligent? In case a restaurant does not comply with the rules, HACCP food safety auditors can revoke or suspend their licences. Similarly, my rental agency without the identity checks should not be able to sign new lease agreements.

On a related note, failed self-regulatory certificate programs demonstrate that certifications are not taken seriously if the penalties are rarely enforced. PCI DSS is probably one of the better-known ones, which is supposed to apply good information security practices to companies processing credit card payments. However, fines are almost never imposed, and data breaches are still rampant.

This is all Theory! But Do These Practices Work?

The three approaches outlined above may sound academic, but they are already working practice. User ratings and certifications protect privacy and security of the Internet everyday, and here is how:

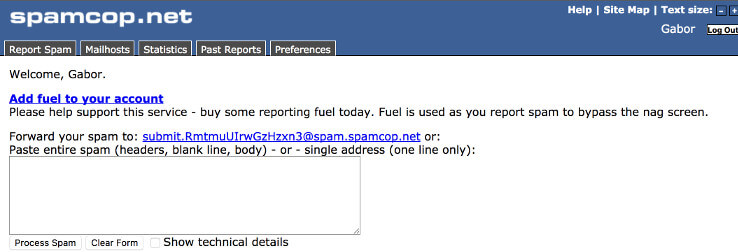

User ratings are used to tackle phishing. A service called SpamCop is a DNS-based email block list (DNSBL) that powers the email filter of a flurry of free (Postfix, Sendmail) and commercial email gateways (Cisco IronPort). Anyone can ‘rate’ phishing emails by submitting them to SpamCop on a voluntary basis. Emails which end up on the SpamCop blocklist are usually blocked by email gateways integrated with SpamCop, and they never reach the recipient’s mailbox.

Internet users are protected by a rating system called Google Safe Browsing, which is a service that allows anyone to flag malicious and deceptive websites. Popular web browsers like Firefox and Chrome are all integrated to this service. Every time you visit a site, your web browser looks the URL up on the Safe Browsing service. If the website is flagged as malicious, the browser rejects to load the page.

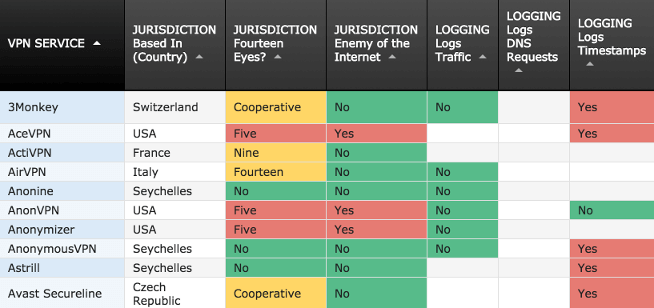

As for independent ratings, the VPN Comparison Chart is an independent certification scheme that works. The maintainer nicknamed ‘That One Privacy Guy’ is essentially a ‘certification body’ who is widely accepted within the privacy community as an authority. His VPN Chart is a checklist of good privacy and security practices. More than two-hundred paid VPN providers are assessed against a hundred of different criterions such as jurisdiction and logging practices. That One Privacy Guy’s Badge Chart shows which paid VPN providers are embracing good privacy practices. The consensus within the privacy community is that the VPN providers from the top of the list are safe to use.

In summary, the Internet community can fight deceptive emails and websites by closing the information gap with these services. As for certifications, the Internet community has accepted a quasi-authority that rates third-party VPN providers by a set of arbitrarily-chosen good practices.

The Information Asymmetry is Solvable

As some of the practical examples from above demonstrate, the information gap between companies which store our sensitive personal data and the consumer is solvable. Principles borrowed from economics, namely education, rating systems, and regulations could be applied to solve the privacy challenges between sellers and customers.

The first option that closes the information gap is education. If customers knew how their personal data is to be managed by a company, they would be able to make more informed decisions. However, it is impractical to train all consumers into full-blown information security professionals to allow them to make these decisions on their own.

Community-powered rating systems, on the other hand, could signal whether a company is responsibly managing personal data or not. Better informed customers could rate the data management practices of a company, which would allow others to make a better-informed decisions. Albeit rating systems are inherently imperfect, issues like fake reviews are well understood and can be managed.

Finally, industry-specific certifications and legislation could ensure that our sensitive data ends up in safe hands. The threat of losing business because of the loss of licence can be a strong incentive to apply good data management practices. For instance, peak bodies, self-regulatory organisations or legislation could specify minimum standards, and companies who fail to tick all the boxes should not be able to carry out the 100 points ID checks. The threat of losing business could incentivise companies to invest into better security and data management practices.

What Is Next?

If you are in Australia, participate in the ongoing consultation process of the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme. If you are living abroad, keep an eye on emerging trends like IoT regulations and GDPR, they are both exciting areas to explore further. As for the 100 points check, it is likely that the AusPost Digital iD™ or other Verification of Identity (VoI) providers will replace or complement the current online identity checking practices.

The author is the president of the not for profit organisation named CryptoAUSTRALIA, whose vision is a society where everyone in Australia has the necessary skills to defend their privacy.

This post has first appeared on the CryptoAUSTRALIA blog

Edits and peer review: Nick Kavadias