Introduction

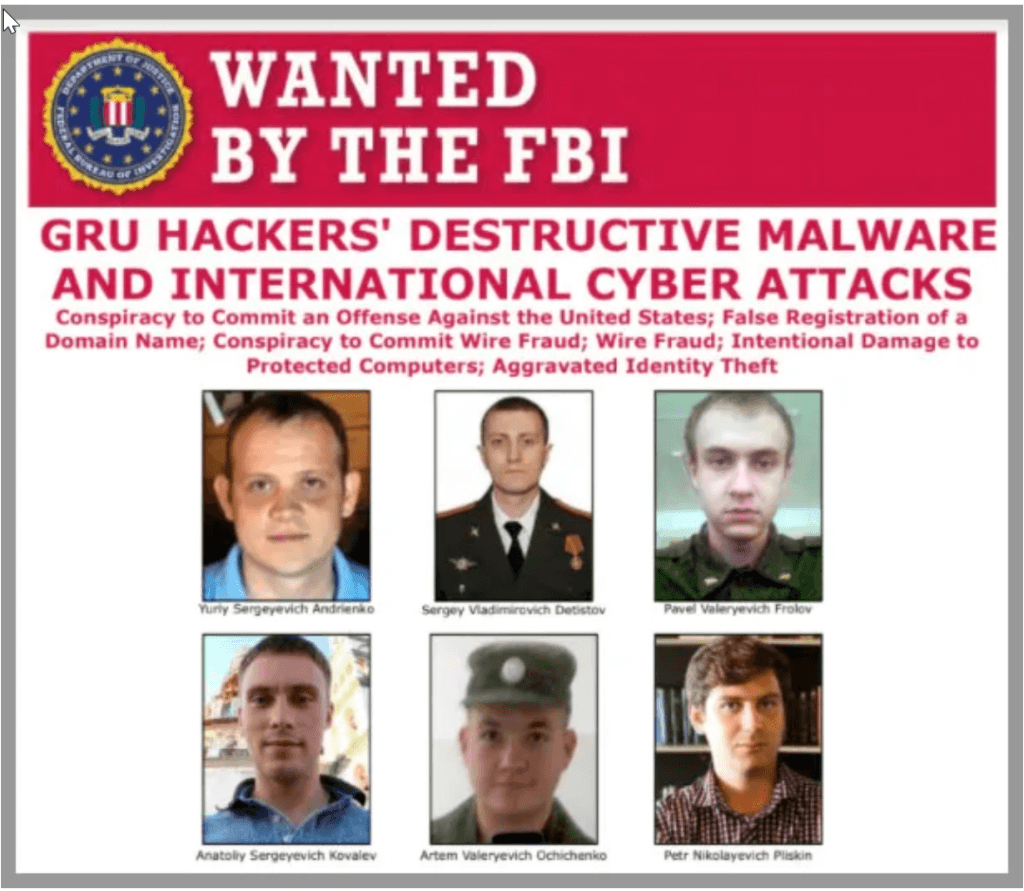

This post is about the 2015, 2016 and 2022 cyberattacks on the energy supply infrastructure in Ukraine. In 2015, the attack of the GRU-sponsored Sandworm hacking team left hundreds of thousands of consumers without power for hours and raised alarms over the security of critical infrastructure worldwide. In 2016 and 2022, two incidents happened again when Sandworm tried to disrupt the power supply in Ukraine.

This article briefly explains the three hacking attempts, the attacker’s motivation, and how the intrusions contributed to the cybersecurity of similar environments.

BlackEnergy: The first strike (2015)

The first cyberattack against the Ukrainian power grid culminated on the 23rd of December 2015, with a simultaneous attack against three power distribution companies in parallel. The fallout of the 2015 intrusion was 230,000 consumers without electricity for one to six hours in freezing temperatures. The US Department of Justice attributes the intrusion to the Sandworm hacking team that maintains close ties to the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).

On the day of the attack, the operators noticed that the keyboard and mouse of their PCs started moving without human interaction and began disabling the circuit breakers of the energy distribution centre. Eventually, the Sandworm team managed to disable circa 30 different substations by disengaging one circuit breaker after the other via a remote desktop session.

In addition, Sandworm amplified the damaging effects with these additional attacks:

- First, Sandworm replaced the firmware of the serial-to-ethernet gateway devices to prevent the operators from bringing the power back online.

- Second, the adversaries activated a wiper malware to cover their tracks and make any recovery attempts difficult.

- Finally, Sandworm launched a denial-of-service attack against the company’s call centre to frustrate its customers.

Despite the extraordinary efforts of Sandworm, the impact was limited as the technical staff could restore the power by operating the circuit breakers manually. However, the supporting actions did have a lasting effect because staff had to operate the breakers in an “operationally constrained mode” afterwards.

How the 2015 intrusion succeeded

Due to the extensive amount of digital evidence that the hackers left behind, forensic experts could reconstruct the chain of events leading up to the final attack. They found that Sandworm utilised the all-purpose BlackEnergy malware to get a foothold within the IT infrastructure and abused the corporate virtual private network (VPN) service to orchestrate the final blow.

First, Sandworm embedded BlackEnergy into a Microsoft Office document and delivered it via spear-phishing. When the victim clicked on the email attachment, BlackEnergy was silently installed in the background. Then, BlackEnergy started gathering passwords and other information from the IT environment and transmitted them covertly to a remote server controlled by Sandworm.

Sandworm then used the stolen passwords to pivot into the ICS network by connecting through the corporate VPN. As the ICS network was not monitored for abnormal activities, Sandworm could perform further reconnaissance and freely manipulate the circuit breakers.

- In summary, experts attribute the success of the 2015 hack to the following malpractices:

- Inadequate end-user awareness training and phishing simulation exercises;

- Undetected BlackEnergy and the reconnaissance activities;

- Data exfiltration events not raising alarm bells;

- Two-factor authentication not protecting the VPN; and

- Incomplete network segmentation.

Although the 2015 outage did not affect many consumers, the hack was a first-of-its-kind setting a worrying precedent for the safety and security of electrical systems everywhere. Shortly after, professionals expressed their concerns over the weak cybersecurity measures of the energy sector in Ukraine and North America. As a response to these concerns, professional bodies have published best-practice frameworks, like the NERC CIP-007-6 and NIST SP-800-9. In addition, as Sandworm left plenty of digital evidence behind, several postmortem reports were born over the following years. The security frameworks and the in-depth reports helped organisations worldwide to build better cyber resilience from similar attacks.

The motivations of Sandworm

Usually, hackers compromise systems because of fame, activism, thrill, challenge, and financial benefits. Oddly, the Sandworm group has never released a statement to explain its goals and intentions. Because of the strong ties with the GRU, however, the motives of Sandworm are likely to involve international relations and political aspects.

The first explanation for the cyberattacks is that the GRU tried to destabilise Ukraine by weakening the citizens’ trust in their government. This interpretation aligns with the Russian hybrid warfare strategy that often involves disinformation, propaganda, and sabotage to undermine democratic institutions in foreign states.

Others speculate that the compromise was a warning to Ukrainian officials not to pursue the nationalisation plans of Russian-owned electricity companies. As a result, the new policy would have dispossessed influential Russian oligarchs with assets in Ukraine’s energy sector. Analysts, however, find this argument unlikely as the plans were shelved by the time of the attack.

A third theory is that the attack was retribution for Ukraine for disrupting the energy supply of the now-Russian Crimea. The power outages in Crimea happened on the 21st and 22nd of November 2015, and they took place one year after the Russian annexation of the area.

In summary, the rationale is likely related to Russian-Ukrainian relations. But, neither the attackers nor any Russian officials explained their intentions.

Cyber intrusions of 2016 and 2022

One year after the 2015 incident, the Sandworm team struck again by hacking into a transmission level substation on the 17th of December 2016. Although the outage left one-fifth of Kyiv in the dark for merely an hour, the attack was far more advanced than before.

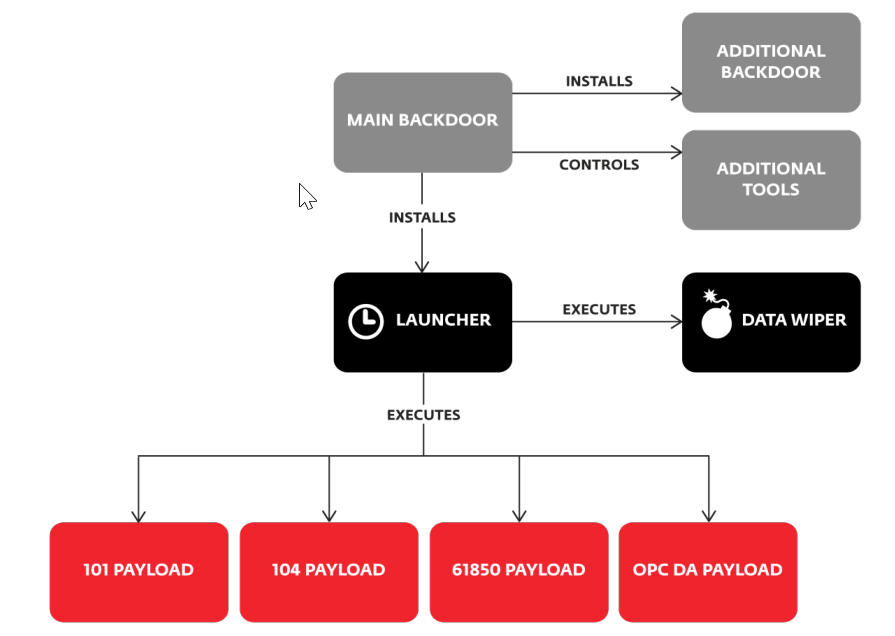

First, Sandworm developed a new purpose-built malware dubbed CrashOverride or Win32/Industroyer. This new cyberweapon was automating the manual efforts of 2015 with code to create chaos on a much larger scale than ever before.

In addition, the Sandworm team tried to disable the overcurrent protection of the protective relays of the substation to inflict permanent damage. If this attempt had been successful, the full-scale power transmission equipment would have permanently been destroyed when the operators re-energised the power distribution system. However, a coding error in the malicious code failed to execute Sandworm’s ambitious plan.

Years later, the 2022 Russian invasion brought a new chapter to the cyber relations between Russia and Ukraine. On the 8th of April 2022, the Sandworm team launched an attack again against a large energy provider in Ukraine to support the ongoing military actions of Russia. In this latest attempt, the offenders tried to tamper with the ICS environment and wanted to destroy the IT environment again. However, the Computer Emergency Response Team for Ukraine (CERT-UA) discovered and thwarted the attack before the logic bombs were activated. In contrast, sources reported that the latest Sandworm operation had managed to temporarily disrupt nine electrical substations in the eastern regions.

Classifying the 2015 attack as cyberwarfare

The three cyberattacks against the Ukrainian power grid can be characterised as an act of cyberwar by several academics. For instance, Stone suggests that war does not necessarily involve lethal actions. Stone points out that even though the prime target of the 1943 US air raids of the Kugelfischer ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt was not humans, the raids are still considered acts of war. Following Stone’s reasoning, the cyberattacks of the power distribution companies could also be acts of war even though the lack of human fatalities.

On the other hand, Arquilla et al. believe that a cyberwar aims to disrupt or destroy an enemy’s information and communication systems. They think that cyberwar is meant to limit the enemy’s ability to follow the intentions and whereabouts of the attacker in the real world. Thus, the Russian cyberattacks can be classified as an act of cyberwar. The power outages made critical communication channels go offline, and Russia timed them to support the military operations in eastern Ukraine.

However, conservative voices call the attacks an act of sabotage instead. For example, Rid argues that war-like events must be potentially lethal, instrumental, and political to be war-like. Therefore, Rid’s definition would classify the Sandworm actions as sabotage because the attacks did not involve any casualties. Therefore, there is no clear right answer to whether the intrusions can be considered acts of war.

Conclusion

Evidence from three cyberattacks against the Ukrainian power grid suggests that the Russian government is actively supporting hacking groups to disrupt the enemy’s critical infrastructure. However, it is unclear what the motivation behind the Sandworm attacks is, and experts are left in the dark to speculate about the intentions behind these attacks.

Despite the ambitious plans, the attacks achieved relatively small success as they could only disable the electricity supply for a few hours. Nevertheless, the failure did not discourage the GRU from supporting conventional military operations with virtual intrusions. In 2022, the Sandworm team launched a brand-new attack against critical infrastructure amid the Russian invasion to support military action in east Ukraine. Even though the preparedness and experience of the Sandworm team, this latest attempt also failed to deliver. The lack of success can be attributed to the readiness on the defender’s side, thanks to the previous incidents in Ukraine. The limited success of the three attacks questions how useful these attacks are considering the years of preparations and the failure in an active military conflict.

Cover photo: Washington Post