Introduction

The terms cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism are both used since the 1990s for describing adverse events in cyberspace. Even though the three-decade history of cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism, academic communities could not agree on a widely accepted definition of these terms and draw a clear line between the two types of cyber events.

On the following pages, we compare the competing definitions of cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism, their differences and similarities, and some recent changes as a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Cyberwarfare

Thomas Rid, a political scientist, relies on the 19th Century definition of conventional war for defining the concept of cyberwar. In 1832, the general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that any aggressive or defensive event must be potentially lethal, instrumental, and political in nature to be an act of war. Rid argues that these three Clausewitz attributes also apply to war-like events in cyberspace. Consequently, Rid points out that cyberwar has never taken place because cyber-attacks in the past were not violent or lethal, instrumental, and political at the same time. He suggests that the more appropriate terminology for describing offensive cyber events is subversion, espionage, and sabotage. In 2022, however, Rid changes his previous viewpoint by stating that an invisible cyberwar is happening between Russia and Ukraine parallel with the conventional military attack in the physical space.

George Lucas shares similar views with Rid’s 2012 paper by stating that none of the large-scale cyber events from the past (apartm from the Stuxnet incident) can be classified as an act of cyberwar. Instead, he argues that events like the 2007 Estonian DDoS attacks, the 2014 Sony Pictures hack, and the 2015 OPM data breach can be attributed to crime, vandalism, vigilantism, or espionage instead.

By contrast, John Arquilla et al. suggests that information-related principles can be applied to traditional military operations. In this work, the authors define cyberwar as the disruption or destruction of information and communication systems of the adversary. In other words, smart weapons, tactical positioning systems, or identification-friend-or-foe (IFF) systems can be jammed or disabled in a cyberwar to turn the balance of force in one’s favour, Arquilla et al. argue.

Similarly, John Stone asserts that cyberwar does exist even when the three Clausewitz criteria of war do not apply. For example, Stone points out that the 1943 US air raids against German ball-bearing factories were inarguably acts of war even though the prime targets were not humans. He suggests that the raid would merely be an act of sabotage per Rid’s 2012 definition of cyberwar. As a result, Stone concludes that cyber-attacks can be acts of war regardless of the prime target of violence.

As opposed to academics, governments seem to take a more pragmatic approach to the definition of cyberwar and its potential consequences. In 2021, President Joe Biden expressed that state-sponsored cyberattacks could escalate to “a real shooting war” with the United States. President Biden reaffirmed his position in 2022 by stating if Russia launches cyberattacks on US companies or critical infrastructure, “we are prepared to respond” – presumably with counterattacks in cyberspace. As state-sponsored cyberattacks would potentially be retaliated with conventional military action, Biden’s policy elevates cyberattacks to war-like levels.

As the media tend to use the term ‘cyberwar’ quite liberally for describing potential and actual cyber-attacks, conservative sources may provide a better definition of cyberwarfare. For instance, the Associated Press Stylebook describe adverse events as ‘cyberwar’ that can result in “significant and widespread destruction”. Similarly, the Cambridge English Dictionary refers to cyber warfare as “the activity of using the internet to attack a country’s computers in order to damage things such as communication and transport systems or water and electricity supplies”.

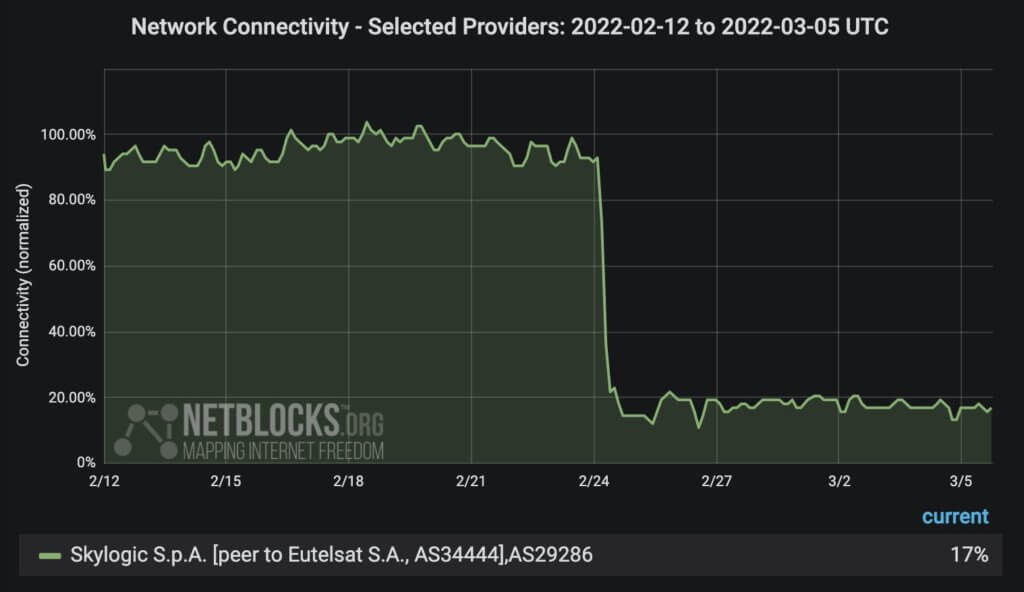

Lastly, the recent 2022 Russian invasion provides a handful of new examples of cyberwar. Rid suggests that the ViaSat and Ka-Sat satellite network outages on the first day of the Russian invasion were acts of cyberwar. As the satellite network subscribers include the Ukrainian armed forces, intelligence services and the police, the outage hindered critical communication channels on the first crucial day of the Russian attack. Even though the cyberattacks have not been attributed to a nation-state yet, Rid concludes that “cyberwar is here”.

Cyberterrorism

In one of the first mentions of cyberterrorism, Kenneth C. White compares cyberterrorists to computer hackers. He describes hackers as “criminally destructive adventurers”, while cyberterrorists are “advanced enemies of a nation state.”. White believes hackers and cyberterrorists are both involved in high-profile computer attacks and only differ in their motivations.

Dorothy E. Denning provides a more detailed explanation of cyberterrorism in her testimony, in which she states, “cyberterrorism is the convergence of terrorism and cyberspace”. Denning argues that the goal of the cyberterrorist is to “coerce a government or its people in furtherance of political or social objectives” by launching attacks against computers, networks and stored information. A cyberattack should generate fear or violence to label it as cyberterrorism.

Several governmental entities have also made attempts to define cyberterrorism. For example, the FBI describes cyberterrorism as a “premeditated, politically motivated attack against information, computer systems, computer programs, and data which results in violence against non-combatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents.”.

Finally, there are similarities between cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism regarding intent and effect. However, Australian Army officer, Aaron Wright, points out two cardinal differences between the two concepts. First, cyber incidents (meant to spread fear and uncertainty) are acts of cyberterrorism, according to Wright. Second, war-like events are also acts of cyberterrorism if they are launched by an unrecognised state, suggests Wright. For example, Russia’s disinformation warfare against the West should be classified as cyberterrorist acts, Wright argues.

Conclusion

Cyberwarfare is a nation-state sponsored attack usually supporting conventional military actions. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine is the latest culmination of the war efforts in cyberspace, and it will likely shape our definition of cyberwarfare and its role in the future.

Cyberterrorism, on the contrary, “could be attacks of anyone with political or social objectives”, meaning nation-states need not sponsor these acts. Although fear and violence distinguish cyberterrorism from cyberwarfare, they share similar objectives regarding physical damage, harm, and injury against humans and property.

Images courtesy of Defence Jobs, F-Secure, USAAF/AFA, Netblocks and NATO.